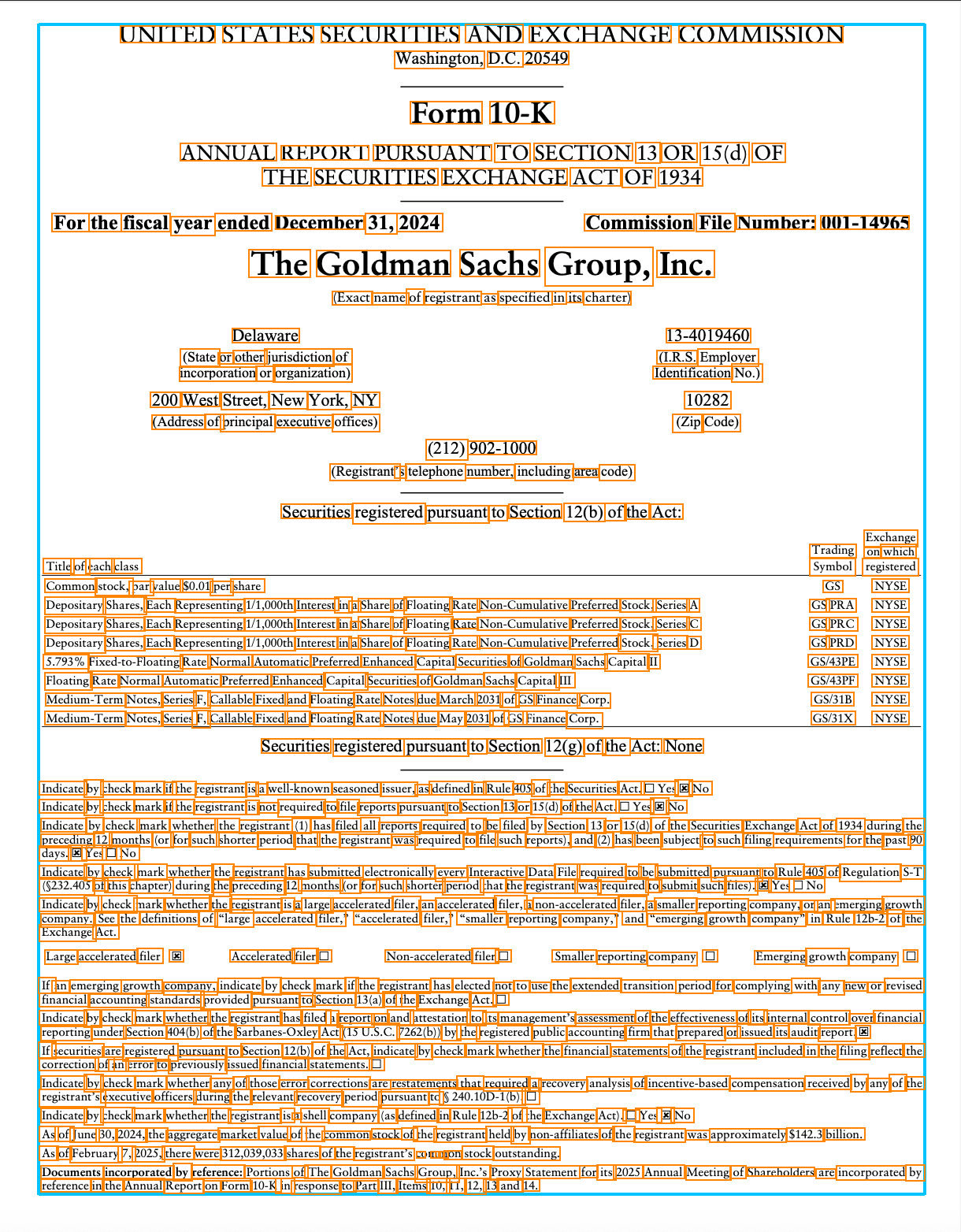

When most people think about document extraction, they think primarily about the text: getting the words off the page, feeding them into a model, and extracting the data they need. In practice, text alone is rarely sufficient. The position of each word on the page often carries information that is just as important as the words themselves, particularly in documents where layout conveys meaning.

Consider a balance sheet with three columns: line item descriptions on the left, current-year values in the middle, and prior-year values on the right. A text-only approach might extract “Total Assets 1,234,567 1,198,432” as a single line. While the values themselves are correct, the text alone does not indicate which number belongs to which year. That distinction is conveyed by spatial position rather than language.

Three Layers of Spatial Understanding

At Pulse, we track bounding boxes at three levels, with each level building on the one below it to capture progressively higher-order structure.

Word-level bounding boxes

Word-level bounding boxes form the foundation. Every word is assigned precise coordinates that define its position on the page. These coordinates make it possible to reconstruct reading order in multi-column layouts, detect table columns through x-coordinate clustering, and align text baselines for cases such as subscripts and superscripts.

Cell-level bounding boxes

Cell-level bounding boxes aggregate individual words into logical units. This layer handles the transition from raw OCR output to structured data by determining which words belong together in a table cell, identifying column boundaries in gridless tables, and grouping multi-line text into a single value. Spanning cell detection also occurs at this level, using the geometric relationship between cell boundaries and the inferred table grid.

Segment-level bounding boxes

Segment-level bounding boxes define higher-level semantic regions such as tables, paragraphs, headers, and forms. This layer enables document zoning by identifying the type of content contained in each region and supports multi-page stitching by preserving continuity when structures extend across page boundaries. When a table begins on one page and continues on the next, segment-level structure ensures that column headers are propagated correctly.

Why This Matters for Accuracy

One of the challenges with text-only extraction is that failure modes are often silent. The extracted table may contain correct numbers and plausible headers, while individual values are associated with the wrong columns. Because the output appears reasonable, these errors can propagate into downstream analysis without triggering obvious warnings.

Word-level spatial precision helps prevent this class of error. When tables lack explicit gridlines, column alignment must be inferred from word positions. Words with similar horizontal coordinates across multiple rows are typically part of the same column, and without access to positional information, this inference cannot be made reliably.

Cell-level structure addresses cases involving merged headers and multi-line values. A header that spans multiple columns needs to be recognized as governing all of the columns beneath it, and the bounding box associated with that header provides the necessary signal to determine its scope.

Segment-level understanding becomes particularly important across page breaks. When a table continues onto a subsequent page, the first row on the new page must inherit column context from the previous one. If that linkage is lost, the extracted rows lose their associations and become difficult to interpret correctly.

Why This Matters for Auditability

Bounding boxes also provide a clear and practical audit trail. Every extracted value can be traced back through the structural hierarchy to its exact location in the source document. When a regulator or reviewer asks where a particular number came from, it is possible to reference not just the page, but the precise coordinates on that page.

This traceability is equally valuable during error analysis. When an extracted value appears incorrect, the associated bounding box shows exactly what the system interpreted. This makes it possible to determine whether the issue arose from an OCR error, an incorrectly detected cell boundary, or an ambiguous layout in the source document.

Universal Across Document Types

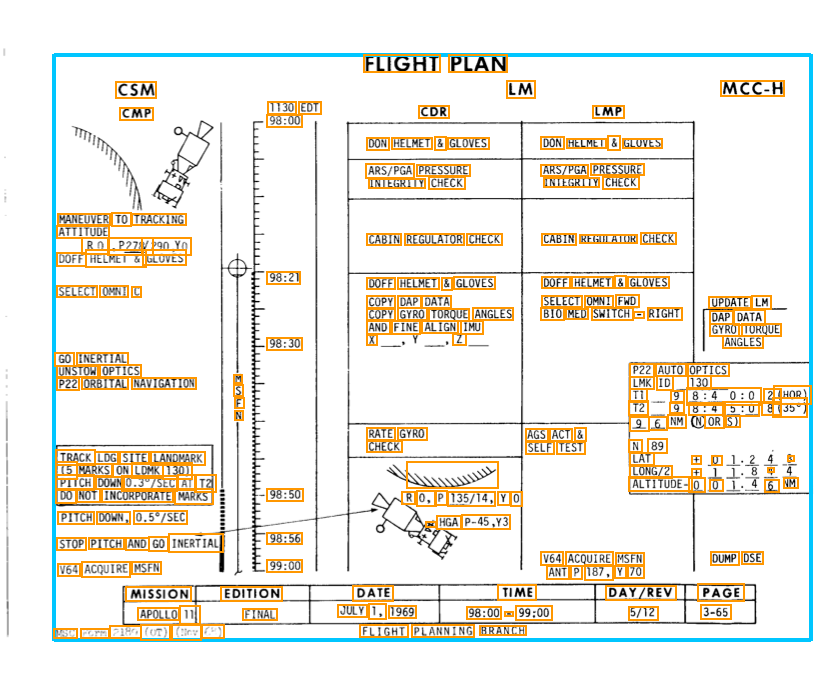

The same coordinate-based approach used for SEC filings also applies to documents with very different layouts.

Operational documents often combine diagrams, tables, free text, and annotations within a single page. Preserving spatial structure is what allows these elements to be interpreted correctly and consistently.

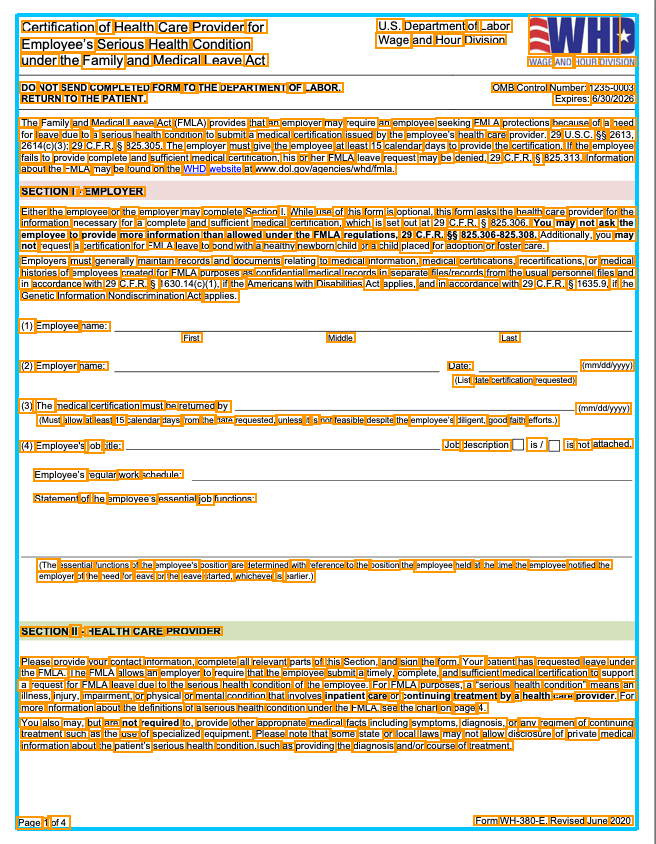

Forms present a similar challenge.

While the visual structure varies across document types, the underlying principle remains consistent: spatial coordinates are what turn a visual layout into structured data.

Organizations that rely on document extraction at scale require results they can trust. That trust depends on accuracy, and accuracy depends on preserving spatial structure throughout the extraction process. Bounding boxes, tracked consistently at every level of the document, provide the foundation for that reliability.

--

Want to see how this works on your documents? Try out public sandbox here, or talk to us about how Pulse handles complex layouts across financial services, healthcare, insurance, and more.

.svg)